Lund University in Sweden has previously reported on Kristian Riesbeck, professor of clinical bacteriology at Lund University and senior consultant, who was contacted by the Ukrainian microbiologist Oleksandr Nazarchuk for assistance in examining the degree of antibiotic resistance in bacteria from severely war-wounded and infected patients being treated in hospital.

Using samples from 141 war-wounded (133 adults wounded in the war and eight new-born babies with pneumonia) it could be shown that several bacteria types were resistant to broad-spectrum antibiotics and that six per cent of all samples were resistant to all the antibiotics that the researchers tested on them.

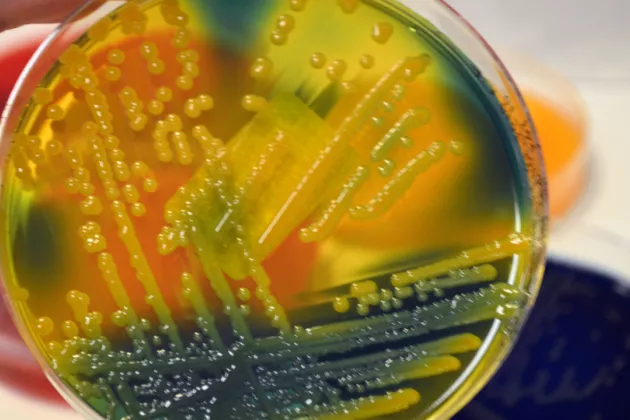

Now, the researchers have published an article in Journal of Infection, in which the researchers have gone on to examine whether Klebsiella pneumoniae has the ability to cause disease in a wider context. Klebsiella can cause urinary tract infections, pneumonia, skin infections in wounds, and sepsis. The researchers used samples from 37 of the patients who had been previously shown to have resistant bacteria. The entire genome of the bacteria was sequenced to examine whether there were genes that can cause resistance.

“All the bacteria were shown to carry the genes that we know are associated with resistance. We saw that one quarter of them were resistant to all the available antimicrobial drugs on the market, these bacteria are said to have total resistance (pandrug-resistant). Infections caused by these bacteria become very difficult, or in some cases impossible, to treat with the medicines we have today,” says professor Riesbeck.

Pandrug-resistant bacteria are an extreme form of antibiotic resistance and a growing concern within healthcare.

The researchers were interested in finding out whether infection could be spread further via the bacteria taken from patients in Ukraine. To examine this, experiments were carried out in mice and insect larvae.

“It was shown that the bacteria types most resistant to antibiotics were also the ones that survived best in mice in connection with pneumonia. Similarly, these bacteria types were so aggressive that they killed the insect larvae considerably faster than the bacteria that were less resistant to antibiotics.”

Genetic sequencing showed that all Klebsiella bacteria with total resistance examined by the researchers carried the genes that make them more virulent.

“In many cases, bacteria lose their ability to infect and cause disease because all their energy is spent on being resistant to antibiotics. But we have perhaps underestimated bacteria: we saw that many of these bacteria types from Ukraine are equipped with genes that make them both resistant and virulent,” says Kristian Riesbeck.

According to professor Riesbeck, this means the bacteria that spread among the wounded in Ukraine will most likely continue to survive and cause problems.

“This is something that will not disappear over time. As long as the patients cannot be isolated and treated properly, the spread of infection will continue.”

Kristian Riesbeck considers the results are frightening, but not unexpected. This is what happens when the infrastructure of a healthcare system collapses. And it applies to Ukraine and other war-torn areas around the world.

“Even though these pandrug-resistant bacteria are fighting to survive our antibiotic treatments, they still have a complete set of genes that make them capable of causing disease. This is surprising for us all and unfortunately a worrying sign for the future.”